Nancy's Tara

by Lynda L. L.

Spring evenings in middle Georgia carry a thick sweetness, dogwood petals drifting like slow snow across the yard while whippoorwills call from the pines. In the open hallway of the Bryan Dogtrot, twenty-one-year-old Nancy Bryan stood barefoot on the worn heart-pine floor, feeling the boards still warm from the day’s sun. It was April 1855, and tomorrow she would leave this house forever.

She pressed her palm against the smooth wide-plank wall, the same wall her small hands had traced as a child while her father’s laughter rolled through the hallway and the smell of frying fatback drifted from the detached kitchen. Fifty voices rose at dawn then—enslaved men and women whose names she knew by heart though the ledgers listed only “Jako” or “Flora.” Their songs still floated in the fields at dusk, low and steady as the breathing of the land itself. Tonight the house felt alive with all of them, as if the walls themselves were reluctant to let her go.

Fifty miles away waited Mayberry Whitehurst and the Gordon plantation—acres of white bolls opening under a sky so wide it hurt to look at it. When Nancy stepped down from the buggy a month later, the heat rose shimmering from the red clay, and Mayberry took her hand with a gentleness that made her heart stumble. That night she lay in a strange bed listening to unfamiliar owls and felt the first small kick of the life they had already begun.

Nine years slipped by in a blur of cotton prices, baptisms, and the sweet weight of babies on her hip. By the fall of 1864, four-year-old Thulia was Nancy’s shadow—bare feet pattering after her through the wide hall, curls bouncing as she begged to “help Mama shell peas.” Nancy would lift her onto the porch rail so she could watch the Macon Road, the child’s sticky fingers tangled in her apron strings.

Then came the sound every Southern woman had learned to dread: distant drums, then hoofbeats, then the low thunder of an army on the march. They saw the smoke first: great black pillars rising above Griswoldville where locals had tried to stop Sherman and failed. Two days later the Yankees were at Gordon. Blue-coated soldiers swarmed the yard like locusts, laughing as they kicked over beehives and shot the milk cow where she stood. An officer with a trimmed beard took Nancy’s parlor for his headquarters, spreading maps across her mahogany table while his boots left red clay on the rug she had hooked herself the winter Thulia was born.

She stood in the doorway and watched flames lick the roof of the gin house. The heat reached her even across the yard, carrying the smell of burning cotton like a funeral pyre for everything she had built. Thulia clung to her skirts, silent now, thumb in mouth, eyes huge and dark. When the last wagon rolled away toward Savannah, only chimneys stood among the ashes. Mayberry walked the fields with shoulders bowed, kicking at blackened clumps that had once been hope. Nancy gathered what remained: silver spoons, a scorched Bible, the cradle quilt her mother had pieced, and loaded them into a borrowed wagon.

She didn't let the tears fall until they had crossed the Ocmulgee River and she saw it: her childhood home, standing stubborn and defiant against the horizon. As her family raced toward them, the realization took hold that they had all escaped Yankee wrath. That evening, as the sun dipped low and painted the sky in hues of amber and rose, they gathered on the front porch, wrapped in the warm embrace of family, the soft breeze carrying whispers of gratitude and newfound peace.

Years later, when Thulia was grown and her own daughter Susan asked what the war had been like, Thulia could only remember the smell of burning cotton and her mother’s arms locked around her so tightly she could feel Nancy’s heart hammering against her cheek.

Susan Myrick carried that heartbeat all the way to Hollywood in 1939. On the Gone with the Wind set she listened to Clark Gable rush his lines and gently corrected him—“No, honey, we let the words sit a minute, like Sunday dinner on the table.” Between takes she told stories of a real Tara that never had marble stairs or scarlet curtains, only a dogtrot hallway where a young girl once stood before the world was set on fire.

Sometimes, late at night in her Atlanta apartment, Susan would open her diary and write about the grandmother she never met yet somehow knew: a woman who walked away from ashes with nothing but a quilt and a fierce refusal to break. The South Susan showed the world was not the moonlight-and-magnolia myth; it was Nancy Bryan Whitehurst holding her daughter in a burning yard, whispering over the roar of flames, “Hush now, baby. We still have each other, and that’s enough to start again.”

Across the Ocmulgee, the old dogtrot still stands. Memories echo within its heart, beautiful in its refusal to let go. On quiet evenings you can almost hear a woman’s voice through the wide-plank hallway, steady as river water running deep: “We will plant again. We will laugh again. The land keeps its promises if we keep ours.”

And somewhere, a long time ago, a little girl with smoke in her curls learned that the truest strength is not in never falling, but in rising every time the world burns around you.

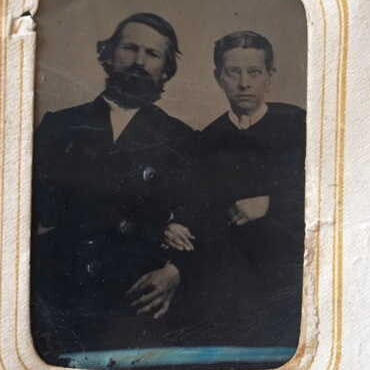

Clark Gable and Susan Myrick on set

Gone With The Wind: An Autobiographical Biography, by Susan Lindsley

Susan's Diary- January 17, 1939

“Today I met Clark Gable. He would not have been worth a whole paragraph by himself before today because I have never liked him. But I did like him when I met him. He is dynamic, quiet, polite, human and fairly bursting with IT. … “How’m I doin’? Falling for the movie idol of a billion femmes. George’s secretary, a darling gal named Dorothy Dawson, called me and said would I come in please. Mr. Gable was in Mr. Cukor’s office. I powdered my face, fixed my lipstick and went in. There sat the God on the sofa beside Cukor and before him stood Lambert, of wardrobe, Plunkett of costume design and two other men with note books. Clark had a dozen sketches before him. He rose as I came into the room – so did George – and G said ‘Miss Myrick this is Mr. Gable.’ I murmured how do you do but he stepped forward, offered his hand, turning on the full force of smile and dimple and said ‘I am so glad to meet you, Miss Myrick.’”